how to add water to a hot water heating system

Everyone who has solar panels on their roof wants to make the most of the electricity they produce, and one of the biggest energy consumers for most households is their water heater. Using solar energy to heat water in the form of a solar hot water system is in fact a better option (financially) than an investment in battery storage – and as such should be the first consideration for most homes.

When it comes to using solar electricity for water heating, there is a surprisingly large number of moving parts and options. Here we aim to break down the various options by your situation so you can decide what action to take.

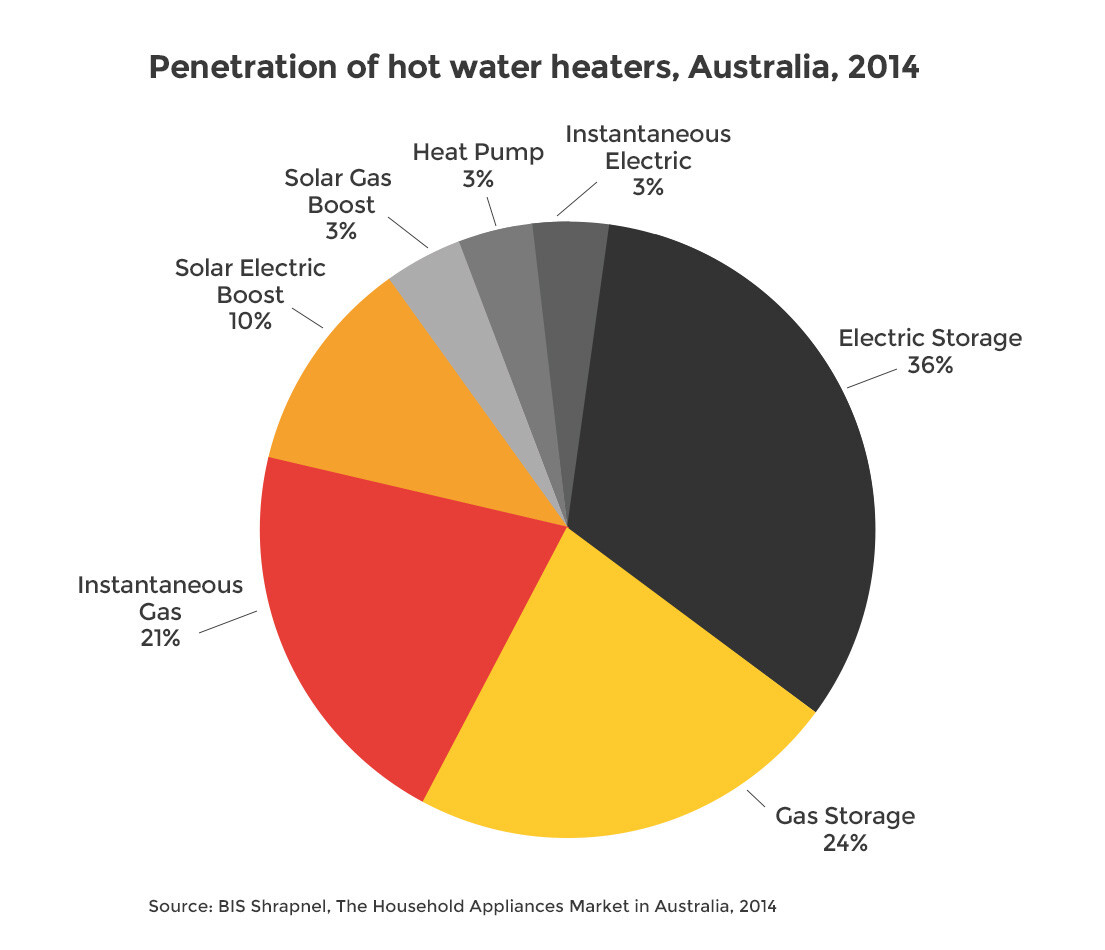

Penetration of types of water heating systems in Australia, as of 2014. (Source: EnergyRating.gov.au).

Penetration of types of water heating systems in Australia, as of 2014. (Source: EnergyRating.gov.au).

What are the moving parts?

In investigating & trying to understand the full range of solar-related water heating options for my own home, it's become clear to me that I'm not the only one left a bit bewildered by the potential complexity of the interplay between solar power and hot water in Australia.

There are up to five different factors that a homeowner might need to consider if they want to get the most cost-effective & efficient water heating configuration possible. For a new-build home or a home where a full energy makeover is underway, all five are likely to come into play, while an older home with existing water & electricity infrastructure may only want to (or have the budget to) change up one or two of them.

These factors are:

- Type(s) of water heating in your home (e.g. electric instantaneous system vs storage tank system vs solar thermal/solar hot water – or some combination of the latter two)

- Tariff type (e.g. flat rate or time of use/flexible rates)

- Whether or not the hot water is on a controlled load/dedicated circuit (where the local electricity network controls when the heating element switches on)

- The size of your solar system and whether you've got surplus energy or not

- How you schedule the heating of your water – if at all (e.g. using a timer, green circuit, solar diverter, or just leave it 'always on')

Let's look at each of these five factors one by one.

Compare Solar & Battery Quotes

What about gas water heating?

Note that this article focuses on electricity and doesn't really talk about gas-based water heating (which in any case is less popular in Australia). If you use gas water heating, then most of this is irrelevant unless you've got a solar booster to go along with it.

1. Types of water heating

Storage/tank hot water:

This is currently the most common type of water heating in Australia (roughly 50-70% of homes depending on how you count it), and is usually done with electricity (about 30-40%) as opposed to gas (about 20-30%). If you don't have solar PV or solar hot water, then all of the energy used to heat your water comes from the the grid; you pay either your main tariff rate for this energy, or you have a controlled load tariff where the rate is a bit lower (more on this below).

If your tank-based hot water system is coupled with a solar hot water system (aka solar thermal – usually evacuated tube or panel type – see below), this is likely to do most of your water heating, with your tank getting topped up by the electricity grid only when sunlight falls short.

An electric hot water storage tank system by Rheem. (Image via Rheem Australia.)

If you've got a solar PV system, on the other hand, the solar energy it produces will only go towards heating your water if:

- Your hot water element is on your regular tariff (i.e. not on a controlled load – see below),

- You've got surplus solar energy during the day, and/or

- You've got a solar diverter that allows you to 'toggle' between your controlled load circuit (whose operational times are decided by the network, not you) and your ordinary/mains electricity (which you can draw from whenever you want, but which you may pay a higher rate for).

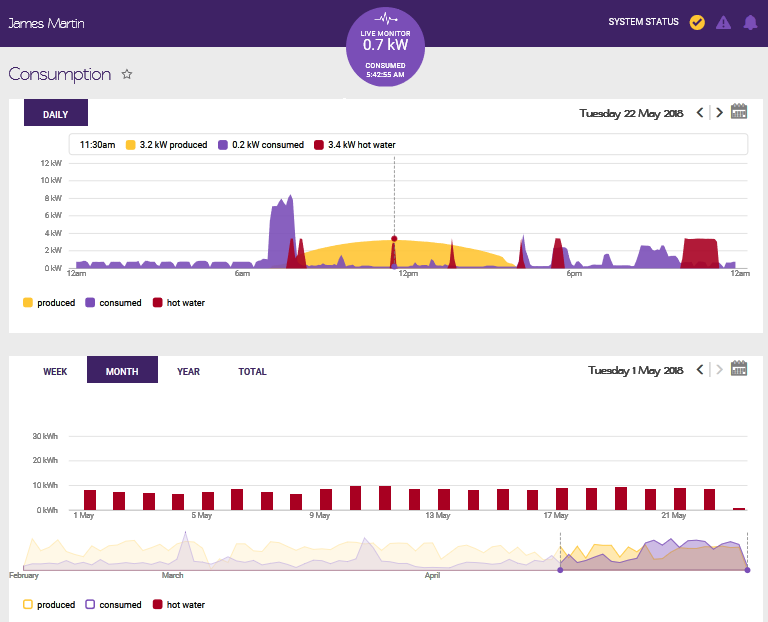

We note here that one of the crucial sub-factors involved is the wattage (or instantaneous electricity draw) of your water heating system. Often, this is significantly higher than virtually anything else in your home. In my house, where we have a small tank, the element uses about 3.6kW, which is just barely 'covered' in the winter months by the 4.4kW solar system on my roof – and even then, only during the prime sunshine hours between about 11am and 2pm.

Heat pump systems: A class of their own

While this article focuses on 'electro-resistive' water heating (which is commonplace in Australian homes), in fact the most efficient type of tank water heating systems are heat pump-based systems. Heat pump hot water systems are dramatically more effective than conventional electric hot water system heaters because they actually draw renewable heat from the air rather than creating heat from electricity.

A heat pump hot water system by Sanden.

If you do not have a heat pump hot water system already, they are well worth considering as a way to improve the overall efficiency of and reduce energy consumption in your home – especially if you're building a new home or looking to replace an older, failing water heating system.

Check out the below resources for further background & guidance on the topic of water heating & heat pumps:

- EnergyRating.gov.au's 'water heaters' section

- CHOICE's guide to efficient water heating

- This article about the potential renewable heat in Australia by My Efficient Electric Home Facebook group founder Tim Forcey

Solar thermal hot water systems

If you've already got one of these on your roof and it's working well, that's fantastic. These systems are great at directly harvesting the sun's warmth to provide you with hot showers – even if they need to be occasionally boosted by mains electricity or solar PV to ensure they're fully topped up.

If you're considering a brand new solar hot water system and have limited budget, however, you may also want to consider getting a heat pump based water heating system coupled with a solar PV system instead. Solar PV is versatile and cost-effective to install (and doesn't require additional plumbing work as solar hot water does), and having a heat pump based system will allow you to easily do most of your water heating using solar PV (provided you've got the right tariff setup – see below).

Example of a panel type solar hot water system by Rheem. (Image via Rheem Australia.)

Example of a panel type solar hot water system by Rheem. (Image via Rheem Australia.)

Tankless / Continuous flow / Instantaneous water heating

If this is the type of water heating in use in your home, then your solar-related options are quite simple (and limited), as the water heating happens on-demand, while you're running hot water.

This means that your only real option for maximising your rate of solar water heating is to try to shift more of your hot water usage to daylight hours – which is only really possible with dishwashers and washing machines that draw hot water (which we don't recommend because they can increase your hot water demand unnecessarily).

For most households, however, hot water is used for showering – and it's highly unlikely that you'll be able to start taking showers in the middle of the day, when the sun is most abundant but most people happen to be out and about!

Example of a tankless water heater by Rheem. (Image via Rheem Australia.)

2. Type of electricity tariff

In Australia, there are two primary types of electricity tariffs: Flat rate & time of use (TOU). Either of these can be used to power a hot water element in conjunction with solar hot water, solar PV and possibly a controlled load tariff (see below).

Whether your home is on a flat rate or TOU tariff depends on your metering setup. Most Australian households are on a flat rate, but it is possible to switch between the two – although there is usually a setup cost of several hundred dollars associated with doing so. (Check your electricity bill to find out which one you're on.)

Below we discuss the implications of each of these for households with a storage tank hot water system. (Note that the below recommendations assume that you do not have a controlled load for your hot water.)

On a flat rate tariff, you pay the same amount per unit of electricity regardless of the time of day that you use it. (A similar tariff is 'block rate', where the rate increases or decreases depending on the cumulative amount that you've used that day, month or quarter). On a flat rate tariff with no solar, it doesn't really matter when you heat your water, but you'll probably want to ensure the tank is fully heated before you take your showers – whether that means heating it overnight for morning showers, late afternoon for evening showers, or both. If you've got solar PV on your roof, heating during the peak sunlight hours of the day (i.e. about 10/11am to 2/3pm) will allow you to take advantage of the solar energy you have available.

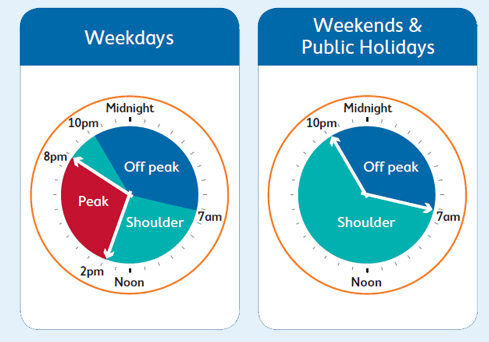

On a time of use (TOU) or 'flexible' tariff, you pay more for electricity during 'peak' times and less during 'off peak' and 'shoulder' times (n.b. that shoulder rates do not apply in every state). This gives you more control of how much it will cost to heat your water, as you can save money by running the element during cheaper off-peak & shoulder times as opposed to more expensive peak times (usually late afternoon into early evening). If you've got solar PV, you can also heat water affordably by running your element while the sun is shining.

Example of a time of use tariff schedule, from Ausgrid in NSW.

Example of a time of use tariff schedule, from Ausgrid in NSW.

Assuming your water is heated on your ordinary flat or TOU tariff (as opposed to controlled load, which requires a separate meter – see below), then you have control over when your water is heated and for how long. Your element will automatically switch off when the water within the tank reaches the temperature set on your tank's thermostat (usually about 40-45C).

Generally speaking, it is not in your best interests to allow water heating 24/4, as this would cause the heating element to come on regularly and unnecessarily throughout the day and night – even if, for example, you only use hot water in the evening. Instead, the best thing to do is set your element to operate on a timer that ensures ample hot water supply at the times when you need it at the least cost.

If you've got solar thermal / solar hot water, this will usually be the cheapest way to heat your water, and the heating will automatically take place throughout the day when the sun is out. Your mains tariff will automatically kick in to make up the difference in temperature (if the SHW doesn't provide enough) as long as you've got your timer set for it to do so.

If you've got a solar PV system, things are a bit more complicated – and interesting – so this situation deserves a detailed investigation (see the 'Timers and Control Options' section below). The simple way to approach it, however, is to set your hot water to run during peak solar production time (about 10am-3pm or so).

3. Controlled load tariffs for hot water: What are they and how do you know if you're on one?

A controlled load (also sometime referred to as dedicated circuit on electricity bills or colloquially as 'off peak hot water') is an electrical device in your home whose operation is controlled by the local electricity network (not your electricity retailer) via a dedicated electricity meter which responds to 'ripple' signals that trigger it to come on.

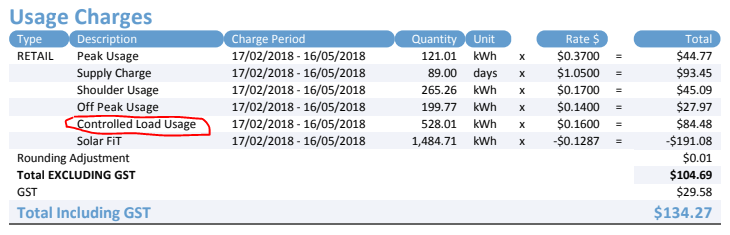

You can find out if your hot water is on a controlled load by looking at a recent electricity bill and checking for a 'dedicated circuit' or 'controlled load'. If you'd like to add a controlled load to a house without one already, it will cost several hundred dollars in metering and electrical work.

Controlled load charges on an electricity bill.

Controlled load charges on an electricity bill.

Hot water elements for storage/tank systems are by far the most common type of device on a controlled load circuit. Being able to control when these operate allows the network to manage electricity demand (or 'network traffic') by ensuring that tens of thousands of heating elements are not all switching on at the same time and overloading the system. The principle is that homes with a hot water storage tank don't necessarily need to heat their water as they use it – it can be heated up hours beforehand and the tank will still be more or less 'full' when the water comes out.

For the slight inconvenience of not being able to exactly control the timing of the water heating (which isn't an issue if your water tank is appropriately sized), households on a controlled load tariff get charged a lower rate for each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of energy that goes into water heating. Types of controlled load tariffs vary by state, but in NSW (which has a similar approach to several other states) there are two types – Controlled load 1 & 2. Controlled load 1 heats only overnight, while controlled load 2 will heat for a chunk of time during the day as well. In Tasmania, on the other hand, the controlled load tariff for hot water heats day and night while still charging a lower rate.

Controlled loads and solar power

If you've got a solar thermal / solar hot water system, your controlled load will switch on from time to time to top up the temperature of your tank, with the end result being fewer kWh of electricity purchased from the grid (on either your mains tariff or controlled load tariff).

If you've got a solar PV system, it will not help you directly offset your water heating costs unless you have a 'booster switch' or solar diverter. In other words, the controlled load functions independently of your home's ordinary consumption unless you've got some sort of device (and appropriately wired metering) that allows it to 'switch over' to your primary tariff.

Note that if your solar feed-in rate (e.g. 12c/kWh) is similar to or the same as your controlled load rate (e.g. 12 or 15c/kWh), it may work in your favour to take no action at all, as each unit of solar that you send into the grid is basically paying for the water heated at other times of day. By doing nothing in this case, you avoid having to splash out on a diverter and/or metering changes. If, however, your feed-in rate is significantly less than the rate(s) you pay for water heating (e.g. 8c/kWh vs 20c/kWh) then it might be worthwhile to look into making physical changes to your setup so you have more control.

Controlled load 2 water heating(in red) displayed on Solar Analytics' monitoring platform. Controlled load energy consumption is not offset by solar PV.

4. The size of your solar PV system

If you're looking to heat your water with a rooftop solar electric system, there are two important things that you need to consider:

- What's the wattage (instantaneous energy draw) of your water tank element compared to the peak output of your solar system? For example, if you've got a 2kW solar system on your roof but have a 4kW element in your hot water tank, the solar system will never be able to fully 'cover' the element's energy draw. This means that as a best case scenario

- How much of your solar energy is going towards non hot water-related loads in the first place? If you've got smaller solar system (e.g. 1.5kW – 3kW), then there's a reasonable chance you're using a lot of the energy it produces for things other than water heating (like doing laundry, running your dishwasher, electric cooking & heating/cooling), which means less energy left over to go towards water heating.

Generally speaking a 4kW or 5kW solar system (both popular sizes these days) will be sufficient for both of the above in most of Australia – although the details will of course vary from case to case.

5. Timer & control options

5. Timer & control options

Once you know what your water heating setup is and how you're charged for your water heating, you'll be ready to decide how to manage & schedule your water heating.

IMPORTANT: For any of the below options to work, it is necessary for your water heating element to be on your mains tariff (i.e. flat rate or time of use, as discussed above), or be able to 'toggle' between your mains tariff and controlled load tariff. If all of your water heating is done only on a controlled load circuit, then none of them will have any impact.

- Set your water heating on a timer. Quite simply, this involves installing a physical timer (manually or remotely controlled) onto your switchboard. This will allow you to set the period or periods during the day that your hot water element switches on.

- Pros: Relatively inexpensive to implement (maybe a few hundred dollars at most). If you check, you might even already have one installed.

- Cons: Timer's aren't foolproof and are a 'dumb' approach to hot water management. For example, if you set your hot water to run during daylight hours to take advantage of the sun, then you could end up paying more for water heating:

- a) if the weather is bad and your solar system doesn't produce as much energy as expected (this is because the instantaneous power requirement of heating element can easily exceed the power production of your solar system); and

- b) if you're on a time of use tariff and scheduling your hot water to come on high solar production times (which happen to coincide with expensive shoulder & peak pricing periods) and your solar produces less than expected (or if you're running other devices in the house which drive up overall energy demand). In this case, you could end up paying peak rates to heat your water instead of with solar or with cheaper overnight off-peak rates. (Read more about this potential issue here.)

- Install a solar diverter. A solar diverter is a device that senses when you've got surplus solar energy and shunts it into your water heating element instead of sending it into the grid. Often they are sold as stand-alone units, but more and more they are also being built into solar inverters at the factory.

- Pros: With most solar diverter brands, the device allow water heating to happen at lower wattages than the element would ordinarily run at – for example, running at only 2.2kW even when it would normally run at 3.6kW. This allows precise use of excess solar energy for water heating – as opposed the the more 'blunt' mechanism of a timer, which just switches the element on at full blast (e.g. 3.6kW) when solar energyshould be available without actually knowing if it really is.

- Cons: Solar diverters can be expensive to install – from $800-$2000, depending on the model and the complexity of installation. Whether the cost is worth it for your home comes down to how much money you spend on water heating; households with large water heating requirements will see better value and shorter payback periods than those with smaller water heating loads. Additionally, the money spend on a hot water diverter could alternatively be put towards a more efficient water heating system.

- Use a 'green circuit'. Green circuits are a concept pioneered by energy management system developers carbonTRACK. A green circuit is in essence a sort of 'smart timer' that is triggered to automatically switch on a load (such as hot water element) as soon as it senses when a solar PV system hits a pre-determined level of power output (e.g. 3.6kW, 5.2kW, etc), and will continue to run that load for as long as it has been programmed to do so. The load will continue to run for a set amount of time (e.g. 2 or 3 hours) regardless of whether the solar system continues to produce at that level of output. If the solar system does not achieve the threshold by a certain time of day (e.g. 1pm), the green circuit will switch on the load anyway to ensure that the home has enough hot water for the evening.

- Pros: As a 'set and forget' solution, this is an excellent compromise between a timer and solar diverter, and with all the additional monitoring capability and management controls that come with carbonTRACK units, it may cost less and offer overall better value than a dedicated diverter. Furthermore, using a green circuit allows you to also take advantage of cheap, overnight off-peak electricity prices, as it also functions as a standard timer.

- Cons: While a bit more effective than a simple timer, a household using a green circuit may fall victim to some of the same problems that come with using a timer. That is, if the green circuit automatically switches on your hot water element (as triggered by the 'solar threshold'), it will not then automatically switch itself off again if the solar production falls due to shading or changes in the weather; this could result in higher overall charges for hot water.

- Leave the water heater 'always on'. Quite simply, this involves turning on your hot water element and letting it run all the time, topping up the heat whenever required (which may be dozens of short bursts throughout the day).

- Pros: The ultimate 'set and forget' solution, this costs nothing to implement and ensures you have hot water whenever required, as the element will automatically switch on whenever it senses that the water inside is not heated to the set temperature on the thermostat.

- Cons: This is also almost certainly the most costly way to heat your water, not specifically taking advantage of available solar energy of lower shoulder or off-peak electricity rates. For anyone concerned with both maximising comfort and whilst also minimising costs, this is least attractive option available.

So what should you do?

If you're considering a brand new solar system, you're in a great position to assess or reassess your home's water heating system. Most solar companies either offer inverters with hot water diverter functionality or install stand-alone diverters or energy management systems alongside solar panel systems. Armed with the options & information outlined in this article, you will hopefully feel confident about talking them with solar companies whose quotes you are considering.

Similarly, if you're looking into ways for putting excess solar energy from an existing solar system to better use within your home (namely, by funneling it into your hot water tank), we hope that this article give you and idea of the different options available to you.

Further resources:

Solar / hot water diverters

Energy management system comparison table

Is battery storage worth it in 2019?

Get a free, instant Quote Comparison:

Compare Solar & Battery Quotes

- About

- Latest Posts

![]()

James Martin II

Contributor at Solar Choice

James was Solar Choice's primary writer & researcher between 2010 and 2018.

He is now the communications manager for energy technology startup SwitchDin, but remains an occasional contributor to the Solar Choice blog.

James lives in Newcastle in a house with a weird solar system.

![]()

how to add water to a hot water heating system

Source: https://www.solarchoice.net.au/blog/solar-hot-water-system-everything-you-need-to-know/

Posted by: farrararkmadesain.blogspot.com

0 Response to "how to add water to a hot water heating system"

Post a Comment